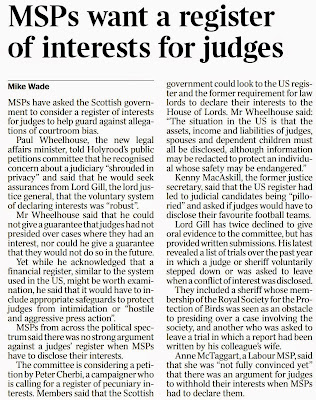

Minister fails to convince MSPs judges wealth & links to big business should remain secret. MSPs from the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee are now deciding their next moves in their investigation of proposals to create a register of judicial interests as called for in Petition PE1458: Register of Interests for members of Scotland's judiciary, after taking evidence from Paul Wheelhouse - the Minister for Community Safety & Legal Affairs.

Minister fails to convince MSPs judges wealth & links to big business should remain secret. MSPs from the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee are now deciding their next moves in their investigation of proposals to create a register of judicial interests as called for in Petition PE1458: Register of Interests for members of Scotland's judiciary, after taking evidence from Paul Wheelhouse - the Minister for Community Safety & Legal Affairs.

The Petition Committee’s evidence session with Mr Wheelhouse, taking place at Holyrood on Tuesday 9 December, published today in it’s entire written record & accompanied by video footage, also heard of comparisons with a US register of financial interests for judges which could serve as a model for any register of judges interests in Scotland.

Petition PE1458 – a proposal to increase judicial transparency and submitted to the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee in late 2012 envisages the creation of a single independently regulated register of interests containing information on judges backgrounds, their personal wealth, undeclared earnings, business & family connections inside & outside of the legal profession, offshore investments, hospitality, details on recusals and other information routinely lodged in registers of interest across all walks of public life in the UK and around the world.

Legal insiders who have studied Mr Wheelhouse’ evidence believe the Minister gave several misrepresentations to members of the Committee about interests disclosures of Scotland’s judges. A Scottish Parliament insider branded Mr Wheelhouse as “anti-transparency” and “a poor substitute for Lord Gill”.

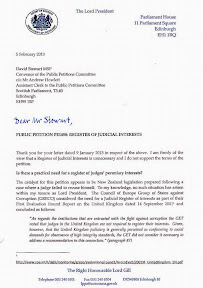

Lord President Lord Brian Gill – Scotland’s top judge has refused several invitations to appear before the Scottish Parliament and explain his opposition to the creation of a register of judicial interests.

Mr Wheelhouse also followed Lord Gill’s lead in criticising the media, implying a register of judicial interests may cause judges some problems if the press find out more about judges secret interests, such as tax avoidance, investments in companies with criminal records, criminal records & convictions, and other matters the judiciary prefer not to reveal to the public.

None of Mr Wheelhouse’ reasons against a register of interests for judges were accepted by members of the Petitions Committee.

It also became clear from admissions by Mr Wheelhouse’ civil servants they and Mr Wheelhouse had not even met Lord Gill, or the new Judicial Complaints Reviewer – Gillian Thompson – who. it was confirmed, had not even bothered to reply to the Petitions Committee request for sight of the latest JCR annual report.

It also came out during questions from MSPs that neither the Minister or civil servants had yet had sight of Lord Gill’s proposed changes to the complaints rules – even though the consultation held by the top judge on rules changes had ended over a year ago.

Input in the debate from new Committee member Kenny MacAskill was also lampooned by parliamentary insiders, noting the sacked Justice Secretary’s attempt to criticise how judges are selected in America, gave little weight to reasons to conceal the secrets of wealthy Scottish judges. Mr MacAskill was rushed in to the Petitions Committee to replace the popular Chic Brodie – who supports transparency and declarations of interests.

Legal Affairs Minister Paul Wheelhouse evidence to Petitions Committee Petition 1458 Register of interests for members of Scotland's judiciary

Judiciary (Register of Interests) (PE1458)

The Convener:The next item of business is an evidence-taking session with the Scottish Government as part of the committee’s consideration of PE1458, by Peter Cherbi, on a register of interests for members of Scotland’s judiciary. Members have a note by the clerk and the submissions.

Nothing has been received from the Judicial Complaints Reviewer. However, the petitioner notified the clerk that the JCR’s annual report to 31 August, which covers the tenure of the previous office-holder, Moi Ali, was published on Friday. Some members might have already received it.

I welcome Paul Wheelhouse, the Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs. He is accompanied by Kay McCorquodale and Catherine Hodgson from the Scottish Government’s civil law and legal systems division.

I invite the minister to make a brief opening statement of approximately five minutes.

The Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs (Paul Wheelhouse): Thank you for inviting me to speak to the committee today.

I welcome this further consideration of the issues around a register of interests for the judiciary and, in particular, the sufficiency of the existing safeguards.

The Scottish Government takes the view that it is not necessary to establish a formal register of judicial interests. That is because, as my predecessor, Roseanna Cunningham, has stated, the Scottish Government considers that the current safeguards are sufficient to ensure the impartiality of the judiciary in Scotland. There is no evidence to date that the safeguards have failed.

There are three important safeguards. The first is the judicial oath, taken by all judicial office-holders before they sit on the bench, which requires judges to

“do right to all manner of people ... without fear or favour, affection or ill-will.”

The second safeguard is the statement of principles of judicial ethics, which states at principle 5 that all judicial office-holders have a general duty to act impartially. In particular, it notes:

“Plainly it is not acceptable for a judge to adjudicate upon any matter in which he, or she, or any members of his or her family has a pecuniary interest.”

The third safeguard is in the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008, which contains provisions to regulate and investigate the conduct of judicial office-holders. Under section 28, the Lord President has a power to make rules for the investigation of

“any matter concerning the conduct of judicial office holders”.

The Complaints about the Judiciary (Scotland) Rules were updated in 2013. In autumn 2013, the Lord President also consulted on the adequacy of the rules. The former Judicial Complaints Reviewer contributed to that consultation. I understand that new rules, together with accompanying guidance, will be published early in 2015. The new rules will simplify the complaints process for all concerned and will clarify what can be properly investigated.

In addition, as members are aware, on 1 April 2014, the Scottish Court Service set up a public register of judicial recusals, following the former JCR’s call for greater transparency and accountability and the informal meeting between yourself, convener, the deputy convener at the time—Chic Brodie—and the Lord President. The register sets out the reason why a member of the judiciary has recused himself or herself from hearing a case. That is a welcome addition to the safeguards that I have already mentioned.

With regard to the complaints system, I am aware of the criticisms that were made in the former JCR’s annual report, which was published last week. I acknowledge the former JCR’s positive influence, during her time in office, over the handling of complaints about judicial conduct. That has contributed to the improvements that are being made to the complaints system.

It is, of course, of vital importance that judges are seen to be independent and impartial. They must be free from prejudice by association or relationship with the parties to a litigation. They must be able to demonstrate impartiality by having no vested interest, such as a pecuniary or indeed familial interest, that could affect them in exercising their judicial functions.

Setting up a register of judicial interests would be a matter for the Lord President, as head of the judiciary in Scotland. The Lord President takes the view that a register of pecuniary interests for the judiciary is not needed and that a judge has a greater duty of disclosure than a register of financial interests could address. The statement of principles of judicial ethics states that a judge’s disclosure duties extend to material relationships, and the new register of recusals addresses that issue.

It is also important to bear in mind the potential downsides of establishing a register of judicial interests. The Lord President said in his written evidence to the committee that it is possible that

“information held on a register of judicial interests could be abused.”

He went on to say:

“If publicly criticised or attacked, the judicial office holder cannot publicly defend himself or herself, unlike a politician. The establishment of such a register therefore may have the unintended consequences of eroding public confidence in the judiciary”.

The Lord President provided further information about the new register of recusals in his letter to the committee of 21 November, which records that all but two judicial recusals were voluntary. There is no record of a case in which a judge or sheriff who has an interest that would justify recusal has had to recuse him or herself after a party has raised the matter. There is, therefore, no evidence to demonstrate that the existing recusal system is not working.

I acknowledge the work that the committee has done in taking forward the issues that are raised in the petition. As the convener acknowledged in the chamber debate,

“the New Zealand bill was ultimately withdrawn on the basis that agreement was reached to improve the rules on recusals and conflicts of interests.”—[Official Report, 9 October 2014; c 64.]

We have similarly had the opportunity for open discussion of these issues. Improvements have already been made in Scotland, such as the introduction of the public register of judicial recusals, and improvements to the complaints rules are about to be introduced. The Scottish Government’s position is that a formal register of judicial interests is neither practical nor necessary.

I am happy to take questions.

The Convener: Thank you, minister. Why should the judiciary be treated any differently from other holders of public office, such as ministers, MSPs or MPs?

Paul Wheelhouse: The point that was made by the Lord President in his letter of 21 November, to which I just referred, is pertinent. I recognise that, as politicians, we have a duty to be accountable to the public who elect us, and we need to be able to demonstrate that we do not have any conflicts of interest. However, the position of the judiciary is somewhat different. As the Lord President outlined, judges are not able to answer for themselves if they are criticised or attacked for their interests, which means that they are vulnerable in that sense. In addition, they or their families might be open to threats or intimidation if property details were registered or if other details were shared that might cause security concerns.

In my previous role, I was aware of Scottish Environment Protection Agency officials who were stalked and harassed on social media, as were their families, and who were being regularly physically and verbally threatened by individuals who were allegedly involved in serious organised crime. I have therefore seen that people of ill intent can attempt to intimidate officials.

The more we protect the privacy of the judiciary in relation to details that could otherwise create security concerns for them, the better, as that will ensure that no one attempts in any way to influence judges’ decisions.

The Convener: How do you respond to the argument from the petitioner and the previous JCR that the current system does not provide individuals with sufficient protection from judicial bias?

Paul Wheelhouse: I am aware of those concerns. I recognise the genuine concerns that have been raised by members of the public, including Mr Cherbi, and, indeed, by committee members during the debate on 9 October. I stress that no one is pointing the finger of blame at any particular judge, but I am concerned to ensure that there is a perception that the judicial system in Scotland is above reproach and that there is no danger of bias in the decision-making process.

The concern that has been expressed has been addressed in a number of respects. We have the JCR and the ability to lodge a complaint against the judiciary if a conflict of interest that has not been disclosed comes to light. There is, therefore, a mechanism for people to raise a complaint, which the JCR can take forward.

As I said in my opening remarks, we have no evidence to date to suggest that anyone has been forced to recuse themselves after someone has raised a conflict of interest. In every case so far, the judge concerned has brought forward their own issues and therefore recused themselves. I am aware of two other cases, one of which involved Sheriff Cowan, who said that her membership of the RSPB might be perceived as a conflict of interest. She put that to both parties in the case, who were given the option to decide whether to allow her to continue in her role or whether she should recuse herself. Ultimately, the defendant in the case asked her to recuse herself.

The process seems to work, and therefore we have no evidence—to date, at least—to suggest that any such bias has been identified in any court case.

The Convener: But how will the parties know that there is a conflict if there is no register of interests? They are not psychic.

Paul Wheelhouse: I take the point. I will take forward these concerns when I meet—for the first time; I have not yet met them—Lord Gill and the new JCR, Gillian Thompson OBE. I will raise the issues in the context of wider discussions and see whether they have any thoughts.

The principle is whether there should be a public register. I note for the record that New Zealand, which was the prompt, if you like, for the matter coming before the Scottish Parliament, has decided to drop the proposal for a public register and instead strengthen its recusal process and complaints procedure. A recusal process and a complaints procedure are already in place in Scotland, and the rules on the complaints procedure are being updated by the Lord President. Those systems are being deployed in New Zealand as well, rather than a public register.

There are concerns about ensuring that there is no undue influence over or harassment of the judiciary as a result of information that they present in a register. In any case, a register could never be completely complete, if I can use that phrase, because it is difficult for a judge to anticipate the full range of cases that might come before them. They could have to declare absolutely everything—every person they know, every organisation they are a member of and every financial interest that they have—yet that might be entirely unnecessary given the case load that comes before them.

The Convener: Exactly the same is true for ministers. You are not expected to declare every single aspect. There is a laid-down procedure for what ministers—and indeed MSPs—have to disclose. No one is asking us to be psychic, but we need to make sure that we follow the rules. If they are good enough for us, why are they not good enough for judges?

Paul Wheelhouse: I take the point entirely. It is entirely appropriate that we declare that information as ministers and MSPs, and, indeed, that MPs do the same. However, we have the opportunity to answer for our actions and get our point across in a way that judges might not be able to—albeit that sometimes it does not feel like that, in terms of the media. As politicians, we can answer for ourselves, and we are usually pretty robust when we do so. It is more difficult for members of the judiciary, and I think that Parliament has to recognise that. They are in a different position and are unable to answer for themselves in the way that we would.

The Convener: I must say that I have not noticed that judges have been slow to come forward in the Sunday Mail recently, but I will leave it there.

David Torrance (Kirkcaldy) (SNP): Good morning, minister. According to the Lord President’s letter to the committee of 21 November, new rules for the judiciary and new guidance are to be published early in 2015. Do you think that they will go some way towards addressing the petitioner’s concerns?

Paul Wheelhouse: That is a very good question—congratulations on being chosen as deputy convener, by the way.

We will have to leave it to the Lord President to provide a detailed response to the issues that were raised by the former JCR and in the most recent annual report. I will look to discuss those issues with Lord Gill when I meet him in due course.

I will bring in Kay McCorquodale to tell you about the detail that we are aware of, but I have every confidence that the Lord President has listened to the criticisms. Moves have already been made to address some of the concerns about the complaints procedure that have been raised by the committee and, importantly, by the former JCR, Moi Ali. Her report raises some concerns about specific cases, and we want to make sure that the complaints procedure addresses all of them. As the minister, I will look to ensure that the procedural weaknesses that have been identified are addressed in due course.

Kay McCorquodale (Scottish Government): Scottish Government officials are in exactly the same position as the minister, in that we have not seen the draft rules. We know that there has been a consultation, and that the JCR fed into it. We anticipate that her concerns will have been addressed. We will meet officials from the Lord President’s private office, and I am sure that they will let us see the rules when they are in a position to share them with us.

John Wilson (Central Scotland) (Ind): Good morning, minister. I welcome you to your new role as the Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs.

You have laid out your defence for not having a register. The petition calls for a register to be set up to ensure that the public can have confidence in the judiciary in Scotland. Earlier this year, an article in The Guardian highlighted problems that had been identified in England and Wales to do with who judges the judges.

Are you 100 per cent confident that every judge and every sheriff will recuse themselves when they have an interest that is relevant to the case that they are considering? The petitioner feels that if we do not have on public record information to tell us whether a sheriff or a judge has an interest in the issue that they are considering or in the individual who is before them, that information might come out at a later date and the person who appeared in court might feel that, in the circumstances, they were unfairly treated or unfairly judged.

Paul Wheelhouse: Thank you for your welcome, Mr Wilson.

You raise some highly significant issues. You asked whether I could give a 100 per cent guarantee that every judge will always recuse themselves appropriately. It would be unreasonable for me to say that I can give such a guarantee, just as I cannot be 100 per cent certain that every MSP, every MP and every person in public life, such as celebrities, will always declare their interests. However, I am confident that the system has procedures to address that—or will have, once the reforms to the complaints procedure have been carried out.

Public confidence in the judiciary is extremely important. You hit the nail on the head as far as the rationale for the debate that we are having is concerned. We want to deliver confidence in the judiciary and to ensure that that is maintained. We tried to establish whether any definitive surveys had been carried out on confidence in the judiciary. To date, we have not been able to identify such a survey but, from a personal perspective, I do not have any sense that there is widespread concern about the judiciary or a lack of confidence in the judiciary. There might be disagreements from time to time over the outcome of particular cases, which is entirely understandable, given that there are two parties to a dispute—a defendant and a prosecutor. However, I do not have the impression that there is widespread concern about the judiciary.

How do we ensure that confidence is maintained, and that the ability of the judiciary to be unbiased is never a concern? We need to have a robust system for recusals in place. We are developing that and, at least to my mind, it seems that the judiciary are using the recusal process appropriately.

Do we have a perfect complaints procedure? Apparently not. I recognise the points that the JCR made in her report. I am confident that the Lord President will reflect on those and will reform the process.

Are there sanctions for those who fail to recuse themselves? Yes, there are. If a judicial office-holder breaches the rules and a complaint is made that they should not have taken a particular case, for example, there might be legitimate grounds for an appeal. In such a case, the Lord President may give the judicial office-holder formal advice about what they have done, or a formal warning or reprimand, which would damage their reputation.

Measures are in place to address such situations should they arise, but I recognise the concern about the fact that the recusal process is shrouded in privacy, to some extent, because it happens within the judiciary and is not open to public scrutiny. I will look to discuss with the Lord President and the new JCR, Gillian Thompson, whether they have any suggestions as to how that might be addressed in future.

John Wilson: You are aware, however, that recusal is voluntary. I welcome the Lord President’s submission on the number of recusals, and you have mentioned Sheriff Cowan’s decision to recuse herself from a case that she was hearing on wildlife matters, but the point is that recusal is still voluntary.

A member of the public or someone appearing before the bench may become aware that a sheriff or judge may have a particular interest in an issue after the case and beyond the period of the appeals process, which is very limited—it lasts three months, as I understand it. The information that a judge or sheriff had a particular vested interest in a case that they were hearing may come out 12 months or two years down the road.

How does it give confidence in the judicial system if people feel that the process for complaining about judges is, as you said, shrouded in secrecy? How do we give the public more confidence that they will be dealt with without fear or favour when they appear before a sheriff or judge?

Paul Wheelhouse: I certainly note the points that you have made. There are three possible scenarios when it comes to recusal.

In the first, people voluntarily recuse themselves. They identify themselves as a risk, and they decide for themselves that, because the issue is so significant, they will voluntarily recuse themselves from the case.

The second scenario involves an element of perception. The member of the judiciary concerned might not believe that the issue will materially impact on their decision, but they offer the information to both sides in the case and leave it to them to decide whether the member of the judiciary should recuse themselves. That has happened twice, to my knowledge, so the system has worked.

The third potential scenario is where a judge or sheriff who has an interest that would justify recusal says nothing about it but has to recuse themselves during the court case, when a party raises the matter. We have no record of that happening so far. Further, to date, no information has been provided to me to indicate that a conflict of interest that has not been identified during a court case has been revealed only thereafter. I appreciate that the recusals process is relatively new, and I cannot guarantee that such a scenario has never happened in the past, but the process is up and running now.

Perhaps we have not emphasised this enough, but the oath that the judiciary must take is quite onerous and clear in requiring members of the judiciary to assess potential conflicts of interest under ethical guidance.

The Convener: The big issue that I and my colleagues have been pushing is that it is assumed that those who appear before a judge have some form of psychic powers. How will they know whether there is a conflict? If there is no register, they will not be aware of it.

Until Chic Brodie and I met the Lord President, there was no system for recording recusals. We made that point to the Lord President, and—in fairness—he agreed to put a system in place, but it came into force only in April. It is only since then that we have been able to assess whether judges have recused themselves. Previously, that was a complete mystery; even recusals were a mystery.

You make out that everything is done fairly and is all above board. However, an ordinary person who appears before a judge does not have a clue whether there is any conflict of interest. That is the key point. We want—or rather, the petitioner wants—a system that is similar to the system for other public officials.

Your only real argument is that judges cannot defend themselves. I am sorry, but that is not a very strong argument.

Paul Wheelhouse: If I may say so, convener, you misrepresent what I said. I did not say that that is the only ground for my view. There are serious concerns about potential influence on the judiciary as a result of revealing their interests in a public register. That would open them up to potentially hostile and aggressive press action, which might apply pressure on them to come down in a particular way in an adjudication.

In some cases—as I said—if members of the judiciary reveal property interests or anything that might give away a physical address, that could put them at risk of physical threats. I have experience of that from working with colleagues in the Scottish Environment Protection Agency who have been threatened by those who are involved in criminal activity.

We must be very careful what we wish for. I take on board your points about the need for transparency. People have to know that the judicial service system is fair, above board and unbiased, and it is entirely right that the committee has taken a strong interest in that.

I appeal to the committee to think about the potential consequences of having a public-facing register that could expose members of the judiciary to undue influence from outside the court process and put them or their families at risk. We must recognise that many members of the judiciary deal with extremely sensitive issues, and often extremely violent people, in the context of their work. That is different from the work of politicians.

It is important to recognise that judges would not have the right to defend themselves—I raised that point, and it is fair for the convener to mention it—but I have wider concerns about the risks that such a register would place on the judiciary.

The Convener: I am a bit conscious of the time. I will bring in Kenny MacAskill before coming back to John Wilson but, before we leave that point, I stress that no member of the committee wants to put judges at risk from any security concerns. Ministers and other MSPs do not reveal their home addresses, and we would have a basic procedure that followed that model. I do not want the minister to misrepresent what I suggest. We would obviously have a register that respected the security concerns of judges; to do otherwise would be a very strange policy.

Kenny MacAskill: I will pursue the issue of public interest. One jurisdiction that has a register is the United States. I am going only by apocryphal tales, but I have heard of potential candidates for the Supreme Court being dissuaded, if not rejected, by House committees in which they have been pilloried. The issue is where the balance is struck. Is there any jurisprudential evidence from the United States on whether justice has been enhanced or whether the public opprobrium wreaked on many potential nominees for the Supreme Court has dissuaded people from going into that theatre at all?

Paul Wheelhouse: Mr MacAskill raises an important point. The petitioner, in his submission of 21 October, drew attention to the register of interests in America. The origins of the United States as a country explain to some degree the formal regulation of Government ethics there.

There has been great attention to the issue since the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, and the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 was brought in to require federal judges to file annual financial reports and provide a full financial disclosure to a committee. The purpose is to expose judges’ financial holdings to public scrutiny, which assists them in avoiding conflicts of interest.

A system is in place in the United States. I have seen some of the reporting on particular judges—I will not quote it here—and the kind of details that are posted. Largely, they are on things such as retirement accounts and life insurance policies. I am not sure whether that adds any value, but it opens people up to being pilloried in the way that Mr MacAskill described and to having every aspect of their financial activities pored over in enormous detail.

When people invest in a general insurance policy or a pension fund, they have no day-to-day involvement in the decisions about how that money is invested. I am not sure how relevant such information is to the process. There was one case in Scotland in which a judge had a pecuniary interest, but it was clear that the decision in the case would not have influenced the value of the shareholding, so it was unlikely that the pecuniary interest would have had any influence.

I do not know whether Kay McCorquodale or Catherine Hodgson has any information of the kind that Mr MacAskill asked for about the negative consequences of having a register in the US.

Kay McCorquodale: I do not have any evidence of that to hand. It is interesting that the register there deals only with financial holdings, as Mr Wheelhouse just explained—it does not cover personal interests or anything else, so it is very narrow. In addition, it covers only federal judges; it goes no wider than that.

Anne McTaggart (Glasgow) (Lab): I welcome the panel and I welcome the minister to his new role. There has been discussion about the differences between our role as elected representatives and the role of judges when it comes to declaring information, but will you expand on why you think that judges should not have to declare information, whereas we have to? I am not fully convinced by that argument.

Paul Wheelhouse: I certainly recognise the point, which the convener also made. I do not want to misrepresent his approach. I am sure that his intent is entirely above board; I do not wish to suggest otherwise.

We have concerns on two fronts. First, as MSPs, we disclose our pecuniary interests and any other things that we perceive might give rise to a conflict of interests. A lot of trust is put in us to declare matters that we believe might influence our decision making as MSPs, whether as ministers, committee members or back benchers. We are trusted to do that, and I believe that the Parliament has a good record on that.

If there is any criticism of an entry in the register of members’ interests, we have the ability to defend ourselves. We have the right to do so and we have the forum to do so—in Parliament, we can put things right on the record. I am not a member of the judiciary and I have no axe to grind in this particular fight, other than that I think that there is an issue of fairness, in that judges do not have the same ability to defend themselves in public as we have.

That is not to say that we have no interest in ensuring that everything is above board. I recognise the points that the committee has made. As I indicated, I will look to get feedback from the new JCR, Gillian Thompson, and the Lord President—when I get the chance to meet him—on what they think is necessary to give the public confidence that, although the system is largely hidden from view, it is operating robustly and that those who are perceived to have a conflict of interests in a case raise that and recuse themselves voluntarily or at least make both parties to the case aware that there is a risk of a conflict of interests and give them a choice.

It is extremely important that the system is seen to be properly and robustly applied and that there is no subsequent criticism of the kind that Mr Wilson fairly raised, whereby someone might have been totally unaware of a conflict of interests that the judge who oversaw their case had and it might be too late to do anything about it under the appeals process. We need to get feedback from the Lord President and the new JCR about how that should be dealt with.

Angus MacDonald: Congratulations, minister, on your new portfolio. You have touched on this, but will you expand on the Scottish Government’s argument that the information on a register could be misleading, as it would not cover all the conflicts that could arise? Do you have a view on the argument that, even if a register is incomplete, it could still have value in increasing transparency?

Paul Wheelhouse: If we want to draw people’s attention to something on the register of interests, we can do that at the beginning of a speech. That relates to Anne McTaggart’s point. We can say, “Presiding Officer, I bring to your attention my entry in the register of interests,” and we can flag up any concerns that members should be aware of. We can do that case by case.

If people had to write their entry in a register in advance, it could be difficult to define exactly what should be recorded. If we are dealing with general cases—not specialist cases in a judicial sense—it is difficult to imagine that the register could cover every scenario in which there could be a conflict of interest, every potential plaintiff or defendant who might come forward in a court case, or every interest that might have to be declared.

The register would have to be either entirely comprehensive or targeted. If people have not anticipated that a case might come forward and have not put something on the register of interests, that could be misleading, because it could look as if there was no conflict of interest; something would subsequently have to be added in advance of a case to ensure that everything was clear. I am not sure that it would be easy to operate such a publicly facing register and to ensure that it fully encompassed all potential conflicts of interest that a judge or sheriff could find themselves involved in.

We have heard about the example of such a register in the US but, as Kay McCorquodale said, it covers only the financial aspects of judicial interests. It does not cover personal relationships or memberships of bodies, which might be an issue. A Scottish register would have to be wider than the one in the US to cover all those potential issues, and it would become difficult to manage. At what point would a judge decide that they knew someone well enough to put that on a register of interests? If you meet someone on the bus, do you have to declare as an interest the fact that you had a friendly conversation with them, or is the register for people with whom you have been lifelong friends? That is difficult to define, and I welcome the committee’s views, but I do not see the case as compelling at this point.

Angus MacDonald: I find it strange that, in America, where it is a requirement to register financial interests, judges do not have to register membership of bodies. I was not aware of that.

Paul Wheelhouse: It appears that there is no requirement to register memberships. I find that slightly odd if the intent is to capture all potential conflicts of interest. We have examples in Scotland of people recusing themselves for being members of organisations. In that sense, we are one step ahead of the US.

Sheriff Cowan recently withdrew from a case voluntarily after having raised the issue with both parties to the case. As she had been a member of RSPB Scotland, and as witnesses from the RSPB were going to appear, there was the risk of a perceived conflict of interests, rather than an actual conflict of interests. She gave the parties the option and they asked her to recuse herself. The system worked well in that case.

We have a system that appears to work, but I appreciate the concerns about the need to ensure that it works every time. If one case goes through where it does not work, that is obviously a concern, but we have no evidence to date that that has happened, so let us look at the glass as being half full.

The Convener: I will let John Wilson in again, because I cut him short earlier.

John Wilson: There is an interesting debate on the constitutional issue of the appointment of Supreme Court judges in the United States of America. I am sure that the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland will look carefully at how judges are appointed to the UK’s Supreme Court and will try to draw on those rules. However, I want to concentrate on the register of interests.

You said in your opening statement that you are aware, because of your experience in your previous ministerial role, that senior officials at SEPA are sometimes stopped and harassed by elements in the community. In your new role as Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, do you intend to introduce legislation to protect public office-holders and their families from being harassed, stalked and approached by people involved in criminal activity? If part of the reason for not having a register is that judges and sheriffs might be stalked and harassed by elements in society, surely we must examine the legislation that protects them from such behaviour.

Paul Wheelhouse: I assure Mr Wilson that, in my previous role, we introduced measures in the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 to protect SEPA officials, which brought their protection into line with that of other key emergency workers.

I take Mr Wilson’s wider point about the judiciary. It would clearly be a criminal offence to do what has been described, but there is a great argument for prevention over cure. Why create a situation where we have to make a new protection for judges when we do not have to put them in that position in the first place? If we can avoid giving away sensitive information that might lead to them being coerced in any way, that will be better than having to resolve the situation after the event by applying legislation, whether old or new.

Mr Wilson makes a fair point, which is that the Government has a duty to protect people in such a situation. I assure him that I will do everything in my power to help to protect members of the judiciary from being threatened. However, it is better to prevent a situation than to have to resolve it.

Kay McCorquodale can give us some guidance on protection.

Kay McCorquodale: As the minister said, this is a serious consideration and we take it into account.

Judicial appointments to the United Kingdom Supreme Court were mentioned. When the Supreme Court was set up, it was decided that it would not be appropriate or feasible for it to have a comprehensive register of interests, because it would be impossible to identify all the interests that might conceivably arise. The court has a formal code of conduct instead. That is similar to our position in Scotland, where we have a statement of judicial ethics.

The Convener: I would like to follow up that point, but I do not want to cut John Wilson off again, so I will let him continue.

John Wilson: Thank you, convener. Minister, you said that you would be wary of having sensitive information put on the public record. Can you define “sensitive information”? Is that just financial information or would it include family relationship information? We could have a judge or a sheriff hearing a case where their son, daughter, mother, father, aunt or uncle was appearing before them to defend or represent someone. Can you define what you mean by sensitive information appearing on a register?

Paul Wheelhouse: I can give examples, but I would need guidance from justice professionals and the police as to what might constitute information that could be risky in terms of modern technology and the ability to attack or damage the interests of individuals. Information on property might be sensitive. The convener made a fair point that personal household information should be kept off any register; that would be sensible if we ever had a register. It would be appropriate to keep residential information private, to protect the safety of the individual and the family and to ensure that it was not a honey pot for those who might want to coerce someone in advance of a decision.

Other sensitive information would be anything else that threatens people’s safety or potentially opens them up to coercion in relation to a court case. We want to protect the integrity of the decision-making process in court, as well as the safety of those making the decisions.

Kay McCorquodale has just pointed out to me that, in the US, the assets, income and liabilities of judges, spouses and dependent children must all be disclosed, although information may be redacted to protect the safety of individuals if they are in danger. That issue has obviously been considered in the US and the approach there might be worth the committee’s consideration.

Kenny MacAskill: It seems to me that it is for those who wish to have a register to define it. What John Wilson said reminded me of a recent high-profile case relating to a football club, in which the judge declared that he was a season ticket holder at another football club. Is it your understanding that that would not constitute a financial interest that he would be required to declare? The judge did not recuse himself but made the information publicly available, which seemed to me the right thing to do.

Do you have any comments on the generality of what would be registered in the proposed register? It seemed to me that the judge in that case was correct to make his declaration. Perhaps the judgment about what to declare should be made with regard to conflict of interest rather than precise rules. Do we expect a judge to declare an interest if he is a season ticket holder at a football or rugby club?

Paul Wheelhouse: Mr MacAskill is absolutely right that we must be reasonable about this. For example, it is left to MSPs to judge what they believe constitutes, or might be perceived to constitute, a conflict of interest and to declare such matters voluntarily, if need be. There is a section in the register of members’ interests where MSPs can voluntarily declare things that might go beyond the minimum requirements, and I am sure that most if not all MSPs use that facility.

I think that we have to rely on the oath and the guidelines for members of the judiciary on what might be, or be perceived as, a conflict of interest and leave it to them to judge what it is appropriate to declare. I commend the example that Mr MacAskill used of the judge making a voluntary declaration so that there could be no perception of conflict of interest, even though that was not strictly required by the terms of the recusals policy.

We have other examples that we should commend of members of the judiciary behaving entirely appropriately by recusing themselves or giving information that would allow others to decide whether they should recuse themselves. I acknowledge and commend the committee’s role in driving forward and achieving a public register of recusals, which is a welcome addition to the process. That register will help to inform those who are involved in court actions of what constitutes a conflict of interest and will refine the process further.

The Convener: Kay McCorquodale spoke about the Supreme Court. You will be well aware that prior to the setting up of the Supreme Court, the Scottish law lords were members of the House of Lords and had to comply with its register of interests. I am not saying that you have suggested that a register of interests is an alien concept for the Scottish legal system—of course it is not, given that generations of Scottish law lords had entries in the House of Lords register of interests. It is not true that the position would be, “Shock horror! We’ll have to fill in a register.” A register is not a new idea, because generations of law lords used a register. It worked well then, so why could it not work for judges and sheriffs now?

Paul Wheelhouse: That is a fair comment. The law lords had to disclose financial interests. Perhaps it is in areas of pecuniary or financial interests that the public could perceive there to be conflicts of interest. For example, if the judge in a damages case had shares in a company that would be affected by the outcome of the case, that would clearly constitute a conflict of interest.

I can understand why financial interests would be declared under the US position and the disclosure rules for the law lords in the House of Lords, but I think that the petitioner seeks something considerably beyond that in asking for full disclosure of information. As I said, some categories of information might put people at risk of intimidation or intrusive press activity, which would be unhelpful for maintaining—

The Convener: For the record, the petitioner is asking for a register of pecuniary interests.

Paul Wheelhouse: Okay. There are certain bounds: we have discussed property assets, and some safeguards would be needed in relation to personal property, as the convener has identified. There are such examples, and I take that point on board. I would have to take such matters to the Lord President and the new Judicial Complaints Reviewer, Gillian Thompson, in order to get their views.

The Convener: I am conscious of time, but it was important to continue that discussion. Does Angus MacDonald have a quick point?

Angus MacDonald: The minister has just covered the point that I was going to raise.

The Convener: We have a high-quality judiciary, and by European—indeed, international—standards it is remarkably free of corruption, so I would not want to see any other view being promoted in that respect.

However, it is important for ordinary men and women who appear before judges that there is an element of transparency. That is what the committee has pursued, and I thank Lord Gill for agreeing to our request for a register of recusals, which was not in place before we raised the matter in April last year.

Paul Wheelhouse: I welcome that too, and I thank you, convener.

Kenny MacAskill: Paul Wheelhouse mentioned that he is due to meet Gillian Thompson, who has previously held the role of Accountant in Bankruptcy and is a senior civil servant. I wonder whether she can bring a fresh pair of eyes to the matter. Are her views known to you, or could they be provided?

Paul Wheelhouse: I am not yet aware of Gillian Thompson’s views on the matter, but I will be seeking them, and I am happy to invite her to relay those views to the committee in due course.

John Wilson: I put on record my thanks to Moi Ali for the evidence that she has given to the committee in the past. I congratulate her on her comprehensive annual report, which was submitted in August and released last week. It makes very interesting reading, and I hope that the minister will, when he meets the Lord President, raise some of the issues that it highlights.

Moi Ali has raised issues about the judicial complaints procedure, and inferred that when a complaint is made against a judge, it disappears into the ether, and that there is no transparency in how those issues are dealt with.

It would be useful to take on board not only the new Judicial Complaints Reviewer’s view on how she will move forward in her role, but the out-going JCR’s experience in the past three years of dealing with the judicial complaints process, in particular with regard to the way in which complaints were dealt with by the Lord President.

I hope that we can move forward and get a system that everybody feels confident will act in the best interests not only of judges, but of the public and everybody involved in the judicial process.

The Convener: I am conscious of time, minister—

Paul Wheelhouse: I will respond briefly to Mr Wilson. I identify with what he said, and I add my own thanks to Moi Ali, albeit that I was not in post when she was the JCR. I welcome her report, and we will discuss the points that it raises with the Lord President and with Gillian Thompson as the new JCR.

We formally received the report only on 23 October, so the time gap is not quite as big as has perhaps been implied.

The Convener: I back up John Wilson’s point. Moi Ali gave excellent and no-holds-barred evidence to the committee, which was refreshing and very useful.

I suggest that we consider the petition again in the new year, when we can reflect on today’s evidence. We need to look in detail at the previous JCR’s annual report, and at the new rules and guidance that I believe will be published by the Lord President early in the new year.

John Wilson: I agree that we should look at the petition again in the new year. I suggest that we tie that in with the release of the information from the Lord President on the new rules, rather than the committee deciding to discuss the issue only to find out that the new rules have not yet been published.

The Convener: Yes, that is sensible.

Kenny MacAskill: It might be useful to hear in due course, either via the minister or directly from the new JCR, what her view is as a fresh pair of eyes.

The Convener: Yes, that is a good point. Do committee members agree that we will do what we have discussed?

Members indicated agreement.

The Convener: I thank the minister and his two colleagues for coming along. Your evidence has been very helpful in enabling us to work out the committee’s next steps, and I appreciate you giving up your time. I suspend the meeting for two minutes to allow for a change of witnesses.

10:54 Meeting suspended.

Scotland’s top judge and Scottish Ministers continue a coordinated opposition the creation of a register of interests. A curious policy for the Scottish Government, considering the First Minister’s words on transparency in other matters. However, a debate in the Scottish Parliament’s main chamber on Thursday 7 October 2014 saw cross party support for the proposal. MSPs overwhelmingly supported motion S4M-11078 - in the name of Public Petitions Convener David Stewart MSP on petition PE1458, urging the Scottish Government to give further consideration to a register of interests for judges.

The parliamentary debate was reported by Diary of Injustice along with video coverage here: TRANSPARENCY TIME: Top judge & Scottish Government told to rethink refusal on declarations of judges as Holyrood MSPs support calls to create a register of judicial interests

Previous articles on the lack of transparency within Scotland’s judiciary, investigations by Diary of Injustice including reports from the media, and video footage of debates at the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee can be found here : A Register of Interests for Scotland's Judiciary

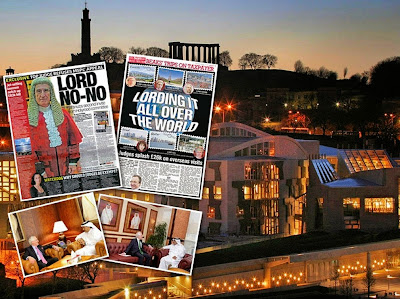

Top judge Lord Gill preferred Qatar state visit to Holyrood’s questions on judicial interests. WHO would have thought Lord Brian Gill - Scotland’s ermine clad top judge - with a long ‘esteemed’ legal career, author of many a court ruling, author of the much watered down Civil Courts Review, an international emissary with an accumulated intergalactic amount of air miles, hand shaker of presidents and, yes, a church music fan, would rather travel to Qatar than appear before MSPs at the Scottish Parliament.

Top judge Lord Gill preferred Qatar state visit to Holyrood’s questions on judicial interests. WHO would have thought Lord Brian Gill - Scotland’s ermine clad top judge - with a long ‘esteemed’ legal career, author of many a court ruling, author of the much watered down Civil Courts Review, an international emissary with an accumulated intergalactic amount of air miles, hand shaker of presidents and, yes, a church music fan, would rather travel to Qatar than appear before MSPs at the Scottish Parliament.