Lord Gill demanded MSPs close probe on register of judges’ interests. A ‘RETIRED’ top judge who twice snubbed giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament and instead flew to Qatar for a taxpayer funded five day state visit - has demanded MSPs close a three year investigation into proposals calling for judges to declare their interests.

Lord Gill demanded MSPs close probe on register of judges’ interests. A ‘RETIRED’ top judge who twice snubbed giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament and instead flew to Qatar for a taxpayer funded five day state visit - has demanded MSPs close a three year investigation into proposals calling for judges to declare their interests.

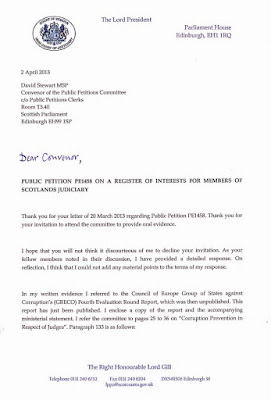

In a stormy session at Holyrood last week, Lord Brian Gill (73) finally sat before the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee and called on MSPs to close down a three year investigation of judges’ interests & business links as called for in Petition PE1458: Register of Interests for members of Scotland's judiciary.

The proposals, widely backed by MSPs after the issue was debated in the Parliament’s main chamber last October 2014 - Debating the Judges - call for the creation of a publicly available register of judicial interests containing information on judges backgrounds, their personal wealth, undeclared earnings, business & family connections inside & outside of the legal profession, offshore investments, hospitality, details on recusals and other information routinely lodged in registers of interest across all walks of public life in the UK and around the world.

During tough exchanges between the ‘retired’ judge and MSPs, Lord Gill got into arguments with members of the Petitions Committee, reflecting his underlying aggressive tone at being hauled before MSPs he twice refused to meet.

In an angry exchange with MSP Jackson Carlaw, Lord Gill demanded to control the kinds of questions he was being asked. Replying to Lord Gill, Mr Carlaw said he would ask his own questions instead of ones suggested to him by the judge.

And, in responses to independent MSP John Wilson, Lord Gill dismissed media reports on scandals within the judiciary and brushed aside evidence from Scotland’s independent Judicial Complaints Reviewers – Moi Ali & Gillian Thompson OBE – both of whom previously gave evidence to MSPs in support of a register of judges’ interests.

Facing further questions from John WIlson MSP on the appearance of Lord Gill’s former Private Secretary Roddy Flinn, the top judge angrily denied Mr Flinn was present as a witness – even though papers prepared by the Petitions Committee and published in advance said so. The top judge barked: “The agenda is wrong”.

And, in a key moment during further questions from committee member Mr Wilson on the integrity of the judiciary, Lord Gill angrily claimed he had never suspended any judicial office holders.

The top judge was then forced to admit he had suspended judicial office holders after being reminded of the suspension of Sheriff Peter Watson.

A statement issued by Lord Gill at the time of Watson’s suspension said: “The Lord President concluded that in the circumstances a voluntary de-rostering was not appropriate and that suspension was necessary in order to maintain public confidence in the judiciary.”

Several times during the hearing, the retired top judge demanded MSPs show a sign of trust in the judiciary by closing down the petition.

During the hearing Lord Gill also told MSPs Scotland should not be out of step with the rest of the UK on how judges’ interests are kept secret from the public.

Questioned on the matter of judicial recusals, Gill told MSPs he preferred court clerks should handle information on judicial interests rather than the details appearing in a publicly available register of interests.

Lord Gill also slammed the transparency of judicial appointments in the USA - after it was drawn to his attention judges in the United States are required to register their interests.

In angry exchanges, Lord Gill accused American judges of being elected by corporate and vested interests and said he did not want to see that here.

However, the situation is almost identical in Scotland where Scottish judges who refuse to disclose their interests, are elected by legal vested interests with hidden links to corporations.

Speaking after the evidence session, legal insiders said: “Lord Gill appeared to have been made Lord President for a day to go into the Scottish Parliament and order the closure of a petition.”

However, after hearing Lord Gill’s evidence, several MSPs on the committee – including Angus MacDonald (SNP) who earlier backed the call for a register of judicial interests – decided they did not want to call the new Lord President to give evidence.

The move goes back on a decision under the Committee’s previous Convener – John Pentland MSP – to call the new Lord President who is still to be named after a secret six month selection process.

Speaking to the Scottish Sun newspaper, Petitions Committee Convener Michael McMahon MSP said the committee would now write to the new Lord President instead.

And, while saying he was impressed by Gill’s ability to defend his corner, MSP Mr McMahon described Lord Gill as displaying “passive aggression” during his evidence before the committee.

The Public Petitions Committee will debate the evidence and demands from Lord Gill at a future hearing on 1st December 2015.

The Scottish Sun reports:

Holyrood axes plan for grilling top judge

Holyrood axes plan for grilling top judge

Exclusive: By Russell Findlay, Scottish Sun 15 November 2015

POLITICIANS have axed plans to grill Scotland's next top judge on secret wealth and business links.

The U-turn came as the former Lord President finally agreed to discuss a judicial register of interests with MSPs.

After tetchy exchanges with Lord Gill, 73, the petitions committee have now dropped the move.

It will instead write to his successor then decide whether to invite them.

Committee chair Michael McMahon said: "Despite Lord Gill's passive aggression, I was impressed by his ability to defend his corner.

"The committee has reviewed its decision to automatically invite the incoming Lord President."

The peer twice snubbed committee invites when he held the £220,655 post.

Legal reform campaigner Peter Cherbi said: "The public is entitled to hear the views of the serving Lord President rather than the retired one."

Evidence of Lord Gill before the Scottish Parliament 10 November 2015

Judiciary (Register of Interests) (PE1458)

The Convener (Michael McMahon): Good morning, everyone. Welcome to the 18th meeting in 2015 of the Public Petitions Committee. I remind all those who are present, including members of the committee, that mobile phones and BlackBerrys should be completely turned off because they interfere with the sound system even when they are switched to silent.

The first item of business is consideration of PE1458, by Peter Cherbi, on a register of interests for members of Scotland's judiciary. The committee will be taking evidence from the Rt Hon Lord Gill, who is a former Lord President of the Court of Session. I welcome Lord Gill to the meeting. He is accompanied today by Roddy Flinn, who is legal secretary to the Lord President. I invite Lord Gill to make a brief opening statement, after which we will move to questions.

The Rt Hon Lord Gill (Former Lord President of the Court of Session): Thank you, Mr Convener, for your welcome. Your predecessor wrote to me in June this year to invite me to discuss with the committee my views on what the petition seeks. I am happy to do that today. It seems to me that the petition raises some straightforward questions as to the purpose of the proposal and the problems that it seeks to deal with, if they exist.

Behind that, in my view, there are wider constitutional issues regarding the position of the judiciary in Scotland. Also, there is a question to be asked: what is the committee's opinion of the judiciary that we have?

I do not want to take up time—I want to leave as much time as possible for the committee's questions. For the moment, I shall simply say that I am not entirely certain what is to go into the proposed register, I am not clear what current problems there are that the register would solve and I am, therefore, sceptical about what it would achieve.

I hope that there will be time for us to take a wider view of the matter and to consider that perhaps the constitutional questions are such that the petition may not be the appropriate way to deal with them. It seems to me that there is a very serious question about why Scotland should wish to be out of step with every other jurisdiction in the United Kingdom, and with New Zealand, which is the example that the petition mentions.

With that, Mr Convener, I am happy to discuss whatever matters the committee wishes to raise.

The Convener: Thank you for introducing your thoughts for our consideration. I will pass over to members of the committee, because my throat may not last very long this morning; I do not want to use it too much.

John Wilson (Central Scotland) (Ind): I wish a good morning to Lord Gill and Mr Flinn. In what capacity is Mr Flinn here today in the witness chair? He works for the Lord President's office, and Lord Gill is a former Lord President. I just want clarity, given that when Lord Gill was Lord President he refused to come before the committee to give evidence. He met the previous convener and deputy convener privately to discuss the petition.

Lord Gill: I can answer that very simply. When I was Lord President, Mr Flinn was my legal secretary and he was closely involved in this aspect of the work of my office. He is here today simply because he is familiar with the documentation. If I need to refer to any documents, he will help me to do so. I think you said that he is a witness: he is not.

John Wilson: It is a matter of record in the paperwork that has been presented to the committee this morning. The agenda says that we will

"take evidence from—

Rt Hon Lord Gill, former Lord President of the Court of Session" and "Roddy Flinn, Legal Secretary to the Lord President."

I wanted clarification on that. I assumed that Mr Flinn was here because he was your legal secretary, when you were the Lord President.

Lord Gill: The agenda is wrong, Mr Wilson.

John Wilson: Lord Gill, I am reading from what I have in front of me. The agenda stipulates "take evidence from". I am sure that in your line of work—

The Convener: For clarity, if Lord Gill wants to defer to Mr Flinn to answer a question, or if a member of the committee wants to ask Mr Flinn a question directly, that will be perfectly in order, in which case Mr Flinn will be a witness. I do not think that it is any more complicated than that.

John Wilson: I am just trying to get it on the record because we had a problem when the

committee previously tried to get evidence. We will return to the issue later.

To get to the heart of the matter, we are discussing a petition that was lodged by Peter Cherbi. In your view, Lord Gill, is a register appropriate or necessary?

Lord Gill: I do not think that such a register is either of those things.

John Wilson: Right. Peter Cherbi has previously provided the committee with various pieces of evidence to justify his position. Since the petition was introduced, the register of recusals has been introduced. We now know of cases in which a judge or a sheriff has recused themselves because they have an interest. There was a situation in which a judge recused themselves because of a conflict that was represented by their membership of RSPB Scotland, which meant that they felt that they could not hear a case.

Part of the difficulty, as I understand it, is that the register of recusals is a voluntary register; it is up to judges and sheriffs to decide to recuse themselves from hearing a case. Surely if we had the type of register that is suggested by the petition, there would be less need for recusal because the interests of the person sitting on the bench in judgment of a case would be publicly available.

Lord Gill: There are two points to make in answer to that. One is that the register of recusals is not voluntary. To the best of my knowledge, the clerks of court are scrupulously accurate in keeping the register and therefore, wherever there is a recusal, you may depend upon its being recorded in the register.

However, perhaps the more important point is that there are countless cases in which the register does not even come into play. You may find in a sheriff court—particularly in the country areas—that the sheriff will say to the sheriff clerk that they should make sure that the sheriff does not get any cases that come to the court involving such-and-such a body or person, because they have a connection. The result is that such cases never reach the sheriff, so the register never comes into play. That has always been the case. After a while, most sheriff clerks will know exactly the sorts of cases to which the local sheriff may have some sort of connection. I do not really see it as a problem.

The other thing of course—forgive me for adding this point—is that what has become very clear from the register of recusals is that the vast majority are related to circumstances that a register such as that which the petition proposes would not cover in any way. For example, if the sheriff sees the defender's witness list on the night before a case and recognises the name of someone who is a close friend, he would immediately recuse himself. However, a register of assets such as the petition proposes would be of no value in a situation like that.

John Wilson: In your opinion.

We have heard from the current Judicial Complaints Reviewer and the previous one, both of whom indicated that they would welcome a register of interests. The current Judicial Complaints Reviewer added that she would like the register to include information about hospitality that had been given or received. Are the Judicial Complaints Reviewers wrong in their opinion that there should be a register, and is the current reviewer wrong in her opinion that the register should include information about hospitality that has been given or received? A recent press article highlighted a situation with regard to sheriffs who were involved in overseas trips. One sheriff in particular has called for all his peers to be removed from their committee because he has accused them of leaking information about sheriffs' overseas trips. Surely if we had a register in which such matters were publicly declared, there would be less need for accusations to be made against sheriffs or judges in relation to their activities in the UK, Scotland or elsewhere in the world.

Lord Gill: The first Judicial Complaints Reviewer was very strongly of the opinion that there should be a register of assets for judicial office holders. As you will obviously infer, I disagreed entirely with her about that. As for the current reviewer, I think that she probably came here to speak about something rather different but was asked about the suggested register of assets and expressed her views. All I can say is that I do not agree with them.

However, I think that in your question you have perhaps rather changed the agenda of this meeting; my understanding is that what we are here to discuss the proposal in the petition that there be a register of judicial office holders' assets and property. If you are now suggesting that you want a register of gifts and hospitality, that is a separate issue that would have to be dealt with separately.

John Wilson: I was referring to comments by the current Judicial Complaints Reviewer, who came to the committee to discuss the petition that is before us this morning. In response to questions that she was asked, she indicated that she felt that there should be a register of interests and that she would extend it to include hospitality that had been given or received. I agree that that would widen the scope of the register that is proposed by the

petition, but the issue was raised by the Judicial Complaints Reviewer in her evidence to the committee.

Lord Gill: I have read her evidence.

David Torrance (Kirkcaldy) (SNP): Good morning, Lord Gill. Can you expand on why you think that the current safeguards are sufficient?

Lord Gill: It is very obvious that, for a long time in Scotland, the judiciary has operated on a basis of integrity deriving from the judicial oath that they take on appointment. The terms of that oath are stark and plain; they are the lamp by which every judge is guided in his judicial path. In the modern era, we have added to that the code of judicial ethics, which is a carefully crafted document that went through a wide consultation process. That code gives every judicial office-holder clear guidance on all the ethical problems that are likely to occur.

The question is: does the Public Petitions Committee trust the judges of Scotland to do what they do with integrity and honour or does it feel that, among the judicial office-holders of Scotland, there are men and women who are liable to act wrongfully? It depends on how you approach the problem. It may be that, if your starting point is a belief that among the judges and sheriffs there are men and women who are capable of hearing cases in which they have a personal interest and therefore are capable of being guilty of misconduct contrary to their oath, I can see that there is an argument for having a register. However, as you can imagine, Mr Torrance, I take the opposite view.

After nearly 50 years in the legal profession, I believe more strongly than ever that the Scottish judiciary are dedicated and committed, honourable and loyal to their judicial oath and that they have integrity. If I had thought that, among the judicial office-holders in Scotland, there were men and women who did not have that standard of honour, I would not have wished to be their leader.

John Wilson: In your term of office as Lord President, how many judges or sheriffs were suspended or removed from the bench for inappropriate behaviour?

Lord Gill: None that I know of.

John Wilson: What about acting sheriff Watson?

Lord Gill: Sheriff Watson was a temporary sheriff—

John Wilson: Acting sheriff.

Lord Gill: Just a moment—may I finish? He was not, as you put it, removed from office. What happened was that a litigation arose in which he was involved and I, in the exercise of my discretion, suspended him from sitting as a temporary sheriff until the matter was resolved.

John Wilson: I go back to my original question, convener. How many sheriffs or judges were suspended or removed from the bench during your term of office as Lord President?

Lord Gill: As I told you, the answer is that I suspended temporary sheriff Watson and I did not suspend any other judicial office-holder. It was not in my power to remove them from office, because judicial office-holders can be removed from office only by a procedure that involves the First Minister and the Scottish Parliament.

The Convener: If there had been a register and that temporary sheriff had registered an interest, would that have helped at all or had any implications for your decision?

Lord Gill: No. You have made my point, convener. That would not have been caught in a register. By the way, we cannot make any judgments of fact about that case because it is still, as I understand it, under litigation. We do not know what the facts are.

Angus MacDonald (Falkirk East) (SNP): Good morning, Lord Gill and Mr Flinn. As we have heard, one of your main arguments is that judges have a different role from that of other public officials. Will you explain in more detail the way in which the role of a judge is different from that of other public officials and why that merits the judiciary being treated differently in respect of a register of financial interests?

Lord Gill: If someone is, let us say, a councillor in a local authority, and they are engaged in the business of the authority, they will be involved in making decisions that involve the spending of council money, the placing of contracts, the purchasing of services and so on. It is perfectly understandable that, when an individual councillor votes on whether a company should be given a contract, it should be publicly known what if any interest that councillor has. Judges fulfil an entirely different function: they administer the law, they resolve disputes between parties and, by their imaginative development of the law, they improve and extend the law, explaining it in their judgments. That is an entirely different constitutional function.

In a devolved Scotland, the ministers, the legislators such as you and the judges, as I once was, carry out their different functions in their own different ways. That is dependent on their doing so in a spirit of mutual confidence in which the three organs of the state carry out the functions in the knowledge that they have the trust of the others. That is why, in Scotland today, our devolved democracy is working so well.

The assumption underlying the petition raises a matter of extreme concern. The petition implies that there are judicial office-holders in this country who are unfit to hold that office. If the committee accedes to the principles behind the petition, that would be regrettable, because it would mean that the committee had evinced its own belief that there are judges and sheriffs who are not to be trusted. I invite you, as a committee, to demonstrate your confidence in Scotland's judiciary. If you were to do that, I am convinced that both you as legislators, and the judiciary, would be all the better for it.

Angus MacDonald: Thank you. It was important to get that fundamental view on the record.

What is your view of the fact that the United States of America has successfully introduced a register of judicial interests? Has the system in the States increased public confidence in the judiciary?

Lord Gill: I do not know that we would want to have a judiciary here that is like the one in the United States. It depends on your personal point of view. I do not give you my view, but I am sure that you can guess what it is.

Angus MacDonald: I will not pick up on that particular point.

Has there been any evidence on the impact that the US system has had on the independence of judges or the way in which the media treats judges in the USA?

Lord Gill: I would be very sorry to see a judiciary in which candidates ran for election and in which candidates' election campaigns were based on fundraising from companies and corporations that might be litigants in their courts. I would also be very sorry if the day ever came where, before appointment, judges had to come before a committee of this honourable legislature for confirmation and for examination of their political, ethical and social views.

Jackson Carlaw (West Scotland) (Con): Lord Gill, I am delighted that you are with us this morning. When the petition first came before us, in 2012, I thought that it was rather vexatious, but we went through our normal process and initiated inquiries, as is our wont. What surprised me, given that you have a record of giving evidence to other committees of the Parliament and given that there is nothing terribly controversial in the evidence that you have given us this morning in response to the petition, was that you felt it inappropriate to comment to the committee at that much earlier stage, before the petition started to gain attention and momentum in the media.

You met the then convener and deputy convener, but only privately—I presume, to say to them what you have said to us today. Unfortunately, that gave wind to those who felt that there was something slightly paternalistic in the suggested approach, which was along the lines of saying, "I am not terribly interested in discussing this. I have told you that I think it is largely a bunch of nonsense. Please accept that to be so and carry on," if I can put it like that. I am interested in knowing what your reluctance was. Also, what did you feel could be said only in private then that you feel able to say today?

Lord Gill: I do not know whether it was you, Mr Carlaw—I think that it may have been you—

Jackson Carlaw: I probably added a bit of colour.

Lord Gill: You said that I looked down upon the hoi polloi.

Jackson Carlaw: I freely admit to adding a bit of colour in order to compensate for the magisterial response that we received, Lord Gill.

Lord Gill: Your remark might have come as a surprise to people who know me. However, that is all water under the bridge and we cannot keep harping on about it forever. The main thing today is to discuss the petition, which is what I am here to do. You have asked the question and I have a jolly good answer for you. Here it comes.

In two detailed letters, I set out my reasons for being against the petition. I hope and I think that I set out those reasons with the greatest clarity. I had no further reasons to add; therefore, I was quite satisfied that I had placed before the committee all the help that I could give it.

I have appeared on numerous occasions before the Justice Committee in this very room, so it is not as though I have an aversion to appearing before committees. I am happy to be here today and I am enjoying this stimulating conversation. However, as I had given you all that I could give you, there was nothing to be gained by my coming here.

I also had to consider the office of the Lord President, which I then held, and my judgment was that it was not a situation in which, under the Scotland Act 1998, it was necessary that I should come here for examination before the committee. That was my view. I am aware that you take a different view and I hope that, in differing on that, we will not fall out.

Jackson Carlaw: I am sure that we will not.

Lord Gill: Thank you for that.

Jackson Carlaw: Obviously, you met the then convener and deputy convener privately to explore the very issues of the advice that you felt you had given us. I only suggest that your doing so created, beyond this committee, an impression that there was a reluctance to bear witness to the advice that had been given or to allow us to explore with you the contrary advice that we had received from the former chair of the JCR, which you have dismissed again this morning.

Lord Gill: No. I think that that is a highly overdramatised view of what I did. It seemed to me that, since there was concern among the committee, it was perfectly reasonable for me to meet the then convener and discuss his concerns. What came out of that was really quite helpful, because I was able to tell him things that he did not know. For example, I told him that, if he wanted to know what all my assets were, he could go to the Scottish courts website and find them. He did not know that. I also told him that I was perfectly happy to institute a recording system for recusals if that would help, and he said that he thought that that would be a good idea. I went back to my office and my staff duly implemented it.

Jackson Carlaw: Okay. I should say that I remain—

Lord Gill: Have you got any questions for me about the merits of the petition, Mr Carlaw?

Jackson Carlaw: I remain broadly sympathetic to the views that you have expressed. I simply say to you that it was unfortunate that we found ourselves in the position that we did. You spoke movingly—

Lord Gill: Mr Carlaw, this is water under the bridge now. I am here to talk about the petition.

Jackson Carlaw: That is why I am moving on.

Lord Gill: Well, please ask me some questions about the petition. That would be the most profitable use of time.

Jackson Carlaw: I will ask questions on the petition and on the remarks that you have made in opening and in your responses to questions. Forgive me, but allow me to frame my own questions rather than have them suggested to me.

Lord Gill: Please do.

Jackson Carlaw: You spoke movingly and with conviction about why you feel that the petition is inappropriate and unnecessary. The leaders or representatives of every profession that has ever been the subject of such a register probably said much the same about the character of the individuals with whom they kept company. That in itself is not an argument against a register.

You said that the register would put us out of step with the rest of the United Kingdom, which is something of a monkey see, monkey do argument. Scotland has led the way on a number of aspects of legislation, and the fact that other parts of the United Kingdom have chosen not to do something is not in itself an argument.

Despite the eloquent way in which you spoke about the character of the individuals who are involved, uncomfortably for us both, perhaps, do we not live in a more cynical age in which transparency and the aims of the petition have become part of commonplace life and something that many members of the public now expect of us irrespective of where we serve?

Lord Gill: You may be right. It may be that the public and perhaps even the legislature are in a more cynical frame of mind than in the past. That might be just an aspect of the modern world. However, I know of no example of a case that such a register would have prevented from occurring. As far as I can see, any problems that are likely to arise in the area are exactly the sort of problems that the petition would not address. I have mentioned the most common one, which is the case in which the judicial office-holder knows one of the parties or one of the witnesses. A register would not pick that up.

The petition also mentions the New Zealand situation. As the committee may know, when the proposal was put to the New Zealand Parliament in February, it was defeated by 104 votes to 16. If the committee does not have the documentation about that, I would be happy to make it available. I read it in preparation for this meeting. That proposal arose from a most unfortunate situation in which a judge in a case owed money to one of the lawyers. Obviously, it was deplorable that such a judge would sit in that case, but you will appreciate that that would not be caught by the proposed register. What it really comes down to is that a register would not meet what appear to be the concerns. On the contrary, there is no evidence base to support the proposal.

Jackson Carlaw: In essence, your argument, beyond all others, is that the objective as established in the petition by the petitioner would not necessarily satisfy the objective that he is potentially trying to seek.

Lord Gill: That is my view.

Jackson Carlaw: Finally, given that you have accepted that we may live in a more cynical age than either of us might wish, is there in your mind something that might arise in the foreseeable future, in the most general terms, that might give further public confidence? You have given us the illustrations of the oath and the process that currently exists. Do you think that those are properly understood by the public in relation to the confidence that they can have in the judiciary?

Lord Gill: Yes, I do. I feel very strongly that the people of Scotland have a judiciary whom they know and trust. That is one of the reasons why one would want to live in a country such as this. It is important that the public should know that the Scottish judiciary enjoys a reputation throughout the judicial world that is out of all proportion to the size of our small nation. The influence that it exerts in judicial thinking is enormous. The Scottish judiciary is admired, is respected and plays its part in the international world of judicial affairs. We should be very proud of that. It is one of Scotland's best assets. It would be a tribute to our judiciary if the committee were to acknowledge that by its decision in the present case.

Hanzala Malik (Glasgow) (Lab): Good morning, Lord Gill. I have to be honest with you: I am very impressed by what you have said to us this morning. I want to ask your opinion on something that no one has raised. If—and I use the word "if" guardedly—there was to be a register, do you think that it could put our judiciary at risk in relation to security and terrorism?

Lord Gill: I do not think so. I do not see that as a serious problem. As you will have gathered from my previous answers, I simply think that it would achieve nothing.

Hanzala Malik: I ask because I think that a register would introduce another layer of information—it perhaps would give more information than is currently available—despite the fact that it might not have a practical role. Would it be wise for us to have that information out there in the open?

Lord Gill: I really do not think so.

The Convener: Short of agreeing with the petition—I know that you are encouraging us not to do that—do you believe that an enhancement of the complaints system could address any concerns that people may have about the interests of a sheriff or a judge when they sit in a case?

Lord Gill: Given the number of cases that go through the Scottish courts in a year, the volume of complaints that come to the Lord President is remarkably small, and very few of those complaints are upheld. There is a very efficient system of investigation. It is carried out thoroughly and effectively, and I do not think that it is in any urgent need of improvement because it is working well. Of course, we have to remember that the role of the complaints reviewer is not to deal with the merits of complaints but to ensure that complaints are handled correctly and that the process is carried out in accordance with the regulations. That is a useful function, and it is very helpful to have a reviewer. However, on the merits of complaints, I think that you may be reassured by me that that aspect is being handled very well.

The Convener: In normal circumstances, who makes complaints? Are they made by defence lawyers or witnesses, for example?

Lord Gill: Very often, the complainer is the losing party in a litigation, which is perfectly understandable. There are very few official complaints, if I can put it that way. Complaints are mostly from members of the public, and we have a very effective system of dealing with them. As soon as they come in, they are immediately assigned to the disciplinary judge, who then reads the papers; if there is a reasonable basis for investigating them further, they are then investigated by an independent investigator. For example, a complaint against a sheriff would probably be carried out by a sheriff principal from another jurisdiction. The matter is gone into very thoroughly, and at the end of the day it comes before the Lord President with a recommendation, which he is free to accept or modify.

The Convener: I suppose the follow-up point is that if someone was to make a complaint, they must already have had a suspicion that something was untoward with regard to the sheriff who presided, in which case it would be irrelevant whether that information was on a register.

Lord Gill: You would be surprised how few of the complaints have any substance to them. When they do, in my experience it tends to be to do with the behaviour on the bench rather than any personal interest on the part of the judicial officeholder. Sometimes judicial office-holders get exacerbated on the bench—you would be surprised.

Angus MacDonald: Clearly, you would like us to take decisive action on the petition. However, is it your view that there would be some merit in the Scottish Law Commission examining the issue in more detail?

Lord Gill: That is not a matter for me. The Scottish Law Commission will draw up its programme of work, and that will then be approved by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice, who may make individual references to the commission on ad hoc topics. It may be that the cabinet secretary would wish to refer the petition to the commission, but that is a matter for him.

Angus MacDonald: You do not have a view on that.

Lord Gill: Not for the moment. Until someone can come up with a specific example of a case where the register would have made any difference, I will continue to take the view that it would achieve no purpose.

John Wilson: You referred earlier to the petition calling only for a register of pecuniary interests. However, the petition actually calls on the judiciary

"to submit their interests & hospitality received to a publicly available Register of Interests."

There are registers in place; registers have been instituted under you as Lord President, such as the public register of recusals and the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service judicial members' shareholding register, which the petitioner kindly furnished us with for today's meeting. Surely the petition has served some purpose. Action has been taken to address some of the issues.

You said that you referred to the register of recusals when you met the convener and the deputy convener of the committee in private. Surely the debate that we have had about the petition has been useful: it has moved the petitioner's issues forward, it has moved the Parliament forward and it has moved the Lord President's office forward.

Lord Gill: I disagree with you emphatically, Mr Wilson. All that the register of recusals has done is to prove exactly the point that I made to the convener at the time: there has not been a single example of a recusal that would in any way be connected to the petition. From my point of view, the evidence has been useful in demonstrating that what I imagined was the case is the case.

The register of interests for members of Scottish courts was in existence long before the petition was lodged, so the petition was not the cause of it.

John Wilson: Thank you.

The Convener: That appears to conclude our questions. Do you want to add anything else following the discussion, Lord Gill?

Lord Gill: No. Thank you very much for inviting me, convener. I thank members for the cordial atmosphere in which the session has been conducted. I have sincerely tried to help the committee, and I hope that what I have said has been helpful. I strongly urge the committee to refuse the petition.

The Convener: I do not think that we will make a final decision on the petition this morning. Does the committee agree that we should draw up a paper to be discussed at a future meeting so that we can collate all the information, including the comments that Lord Gill and others have made, and make a final decision at a future meeting?

Members indicated agreement.

John Wilson: I am sorry, convener, but we indicated at a previous meeting that we would try to invite the new Lord President to give formal evidence to the committee when they had been appointed. I am not sure whether the committee is still of a mind to wait for the appointment of the new Lord President and invite them. The new Lord President might have a different opinion from that of the former Lord President in giving evidence before the committee.

The Convener: I am open to whether the committee wants to do that. I was not party to the previous conversation, so I do not know what members agreed.

Hanzala Malik: I am happy and feel that I am in a position to make a decision, so I do not need any more meetings on the matter—

Angus MacDonald: Given the situation that we found ourselves in with the previous Lord President, perhaps some written evidence from the new Lord President would suffice rather than our asking him or her to appear at the committee.

Jackson Carlaw: There is a distinction between the petition that we are considering and some of the more general issues that have arisen during our consideration of it. The evidence that we have heard this morning is quite compelling in relation to the decision that we will arrive at on the petition. What we might suggest by way of any future examination of the broader issues is separate. I think that I now have the evidence that I require in order to arrive at a determination on the petition.

The Convener: I see most members of the committee nodding at that. It has been suggested that we bring a paper to a future meeting and make a decision then, having collated all the information that we have gathered. I do not see any desire among members to seek any further information or to wait until we can get a response from the new Lord President. I do not think that there is any demand for that.

Angus MacDonald: My comments were based on John Wilson's suggestion that we ask the new Lord President to appear before us, which I do not think would be helpful. I agree with colleagues that I now have sufficient knowledge to make a balanced judgment.

The Convener: Okay. We will bring a paper to a future meeting and debate the information that we have so far collated. Is that agreed?

Members indicated agreement.

The Convener: I thank Lord Gill and Mr Flinn for attending this morning.

Lord Gill: Thank you, convener. I thank the members of the committee, too.

Meeting suspended.

Previous articles on the lack of transparency within Scotland’s judiciary, investigations on judicial interests including reports from the media, and video footage of debates at the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions Committee can be found here : A Register of Interests for Scotland's Judiciary