MSPs hear of little help for Scots Party Litigants in Supreme Court appeals. MEMBERS of the Scottish Parliament's Petitions Committee were told earlier this week that measures put in place by the Faculty of Advocates to help Party Litigants raise appeals in civil court cases to the UK Supreme Court – measures which require signatures from two counsel for a Party Litigant’s appeal to proceed, are mere “window dressing” and only serve to further obstruct or block access to justice for people who do not have legal representation.

MSPs hear of little help for Scots Party Litigants in Supreme Court appeals. MEMBERS of the Scottish Parliament's Petitions Committee were told earlier this week that measures put in place by the Faculty of Advocates to help Party Litigants raise appeals in civil court cases to the UK Supreme Court – measures which require signatures from two counsel for a Party Litigant’s appeal to proceed, are mere “window dressing” and only serve to further obstruct or block access to justice for people who do not have legal representation.

Kathie Mclean Toremar, who took her Petition 1504 to the Scottish Parliament’s Petitions Committee this week in a quest to obtain reform to the way in which the legal profession make life difficult for unrepresented party litigants to appeal against decisions taken in the Court of Session, detailed the difficulties faced by those who do not have expensive legal teams in place to represent their cases before Scotland's judiciary. The petitioner also revealed to MSPs that the average length of case for the majority of party litigants in Scotland is a shocking 11 years.

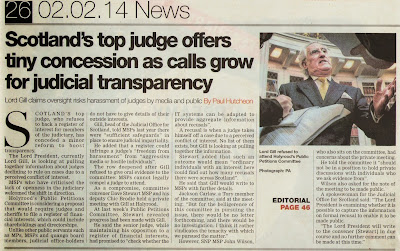

And it emerged in answers to further questions from MSPs that Scotland’s top judge Lord President Lord Brian Gill - famed for his own sharp criticism of the Civil Justice system and his Scottish Civil Courts Review can only manage to direct people with no legal representation or experience of the law to a web page, rather than provide help or answers to why no party litigant has ever been able to approach the Supreme Court after enduring lengthy, bruising encounters in front of Scotland’s highest court, the Court of Session.

Mrs Mclean Toremar, who has been through a prolonged & arduous case in front of Scotland’s unsympathetic judiciary told an amazed Petitions Committee: “I approached Lord Gill, but he simply sent a letter from his secretary telling me to go www.supremecourt.com. I did not ask for legal advice and I did not ask any unusual questions. I just asked about paragraph 1.8, but he would not answer me.”

In an attempt to secure a fair hearing for her own legal case, Mrs Mclean Toremar also revealed to MSPs she had tried thirty eight different solicitors, all recommended by the Law Society of Scotland in an attempt to secure a fair hearing for an appeal against a decision. However, every single solicitor out of the 38 refused to take the case on, citing reasons including “conflict of interests, lack of funding, too many hurdles, and, last but not least, the fact that the pursuer in the appeal has been a party litigant, in relation to which the legalities are a minefield that a solicitor would be reluctant to enter.”

Prior to questions from MSPs in relation to the petition, the Petitions Committee Deputy Convener Chic Brodie criticised the way in which the Scots legal establishment fails to deliver information or help for those who need access to the courts.

Mr Brodie said: “I will begin with a general point, which does not relate only to the Public Petitions Committee. I am very concerned about how hard it is to get information out of the legal system in Scotland. Given that a number of approaches have been made and that hardly any replies have been received, I wonder what on earth is going on and how our legal system is being administered. People should at least have the decency to provide a reply, whether we are talking about the Lord President, the cabinet secretary or whoever. I leave that point lying.”

In response to questions from members of the Petitions Committee, Mrs Mclean Toremar also referred to a response from the Faculty of Advocates to the consultation on the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill which is soon to be heard by the Scottish Parliament’s Justice Committee. In that response, the Faculty of Advocates said it found Party Litigants “Burdensome” and confirmed it was aware party litigants have difficulty with obtaining signatures from counsel.

MSPs also heard evidence from the petitioner, that so far, not one party litigant from Scotland has ever been granted the right to appeal to the Supreme Court, so they cannot fulfil the criteria for making an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

The Scottish Government have recognised there is an issue in how party litigants appeals are dealt with in Scotland and have included ‘some’ reforms in the forthcoming Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill. However the current proposals on offer from the Scottish Government do not go far enough and apparently do not even mention the phrase “party litigant” and in response to questions from David Stewart, the Convener of the Petitions Committee, Mrs Mclean Toremar said the proposals from the Scottish Government would not solve the problems raised in her petition.

Video footage and the official report from Tuesday’s Petitions Committee discussion of Petition 1504 by Kathie Mclean Toremar :

Petition PE1504 by Kathie Mclean Toremar on party litigants civil appeals to the Supreme Court

Supreme Court (Civil Appeals) (PE1504)

The Convener: The next item of business is consideration of one new petition, PE1504, by Kathie Mclean-Toremar, on party litigant civil appeals to the Supreme Court. As previously agreed by the committee, we will take evidence from the petitioner. Members have a note by the clerk, the Scottish Parliament information centre briefing and the petition.

I welcome the petitioner and Gordon Mclean to the meeting. I invite Ms Mclean-Toremar to make a short presentation of approximately five minutes to set the context for the petition, after which I will start with some questions and then my colleagues will ask additional questions.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. I hope that you understand that the petition is about not just me but a gross imbalance in the law regarding all persons in Scotland who find themselves being a party litigant—that is, someone who has to represent themselves in court. We are lucky enough to live in a democratic society in which that is possible.

As I said in my petition, in “A guide to bringing a case to The Supreme Court”, paragraph 1.8, which is headed “Appeals from the Court of Session in Scotland”, states that, although “permission to appeal is not required from an interlocutor of the Inner House of the Court of Session”, the appeal “must be signed by two Scottish counsel”.

That is where the flaw is.

As we all know, a party litigant is a person who, for whatever reason, such as a lack of funds for a solicitor, represents themselves. Nowadays, people are more likely to represent themselves because of a lack of funding for solicitors from the Scottish Legal Aid Board. I myself have seen solicitors demonstrating about the issue. We will have a situation in which more and more people will be forced to represent themselves in court.

When a party litigant represents themselves in the Court of Session, loses their case, then appeals and loses that appeal—I learned through a freedom of information request that there are no statistics on how many party litigants have won their case in the Court of Session—they are also then denied the right to appeal to the Supreme Court, which, according to the European Court of Human Rights, is deemed to be the highest court in the United Kingdom. On the Court’s website, which is www.echr.coe.int, frequently asked question 26 states that an individual must have taken their case to the highest court in the land before they can put it to the European Court of Human Rights.

The fact is that people are being denied their human rights; in this case, the relevant article is article 6, on equality of arms. Everyone deserves a fair hearing. We should be on a level playing field, not divided between the have and have-nots in society. Party litigants lose their right to appeal because of paragraph 1.8, which states that two Scottish counsel must sign the appeal, while the experience of all party litigants is that they cannot approach Scottish counsel in their chambers or in the Court of Session, and certainly not at the advocates library. The only way to approach counsel is through a solicitor, which is where the even larger difficulty lies.

The solicitor has only 42 days to read a case that might have been going on for many years. They then need to speak to two counsel and have them read the case, print their opinion and apply for an appeal to the Supreme Court. Although in theory that process can happen, in practice it cannot and does not happen. Legal aid has to be applied for, which takes time. If legal aid is granted, the solicitor can then contact counsel—I said “if” it is granted; the committee should please take into consideration the cuts to legal aid.

The real problem is that solicitors are wary of taking on a case at such a late stage. As part of my research, I obtained a list of 38 solicitors via Law Society of Scotland recommendations.

Having telephoned all 38 with the scenario I have just described, I found that not one of them was willing to take on such a Herculean task. The reasons cited by many of them included conflict of interests, lack of funding, too many hurdles, and, last but not least, the fact that the pursuer in the appeal has been a party litigant, in relation to which the legalities are a minefield that a solicitor would be reluctant to enter. It is not the solicitors’ fault; it is the fault of paragraph 1.8, which denies party litigants their rights.

In paragraph 6 of its response to the consultation on the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill, the Faculty of Advocates states that it knows that party litigants have difficulty with obtaining signatures from counsel. It goes on to say:“It has also become increasingly burdensome. The number of such cases has been increasing: between 2005 and 2010 the Faculty received five such requests from party litigants”.

That is five requests in five years. “Burdensome” is defined as heavy, onerous, troublesome and hard to deal with, so we can deduce that the faculty does not think highly of party litigants I am still waiting for a response from the Faculty of Advocates to my freedom of information request about how many party litigants it has helped to appeal to the Supreme Court, but I have also contacted the Supreme Court and I already know the answer. Not one party litigant from Scotland has ever been granted the right to appeal to the Supreme Court, so they cannot fulfil the criteria for making an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

Paragraph 1.8 denies a party litigant the right to appeal to the Supreme Court and to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights. That is a blatant human rights issue. The theory is there but, as I say, the practicalities deny a party litigant the right of appeal. Everyone must be treated equally, with fairness and respect. The current situation contradicts the Human Rights Act 1998 severely.

This is a flaw in Scottish justice. The system that is in place is not fit for purpose. It places insurmountable barriers in the way of the party litigant. That happens in any civil case, and civil appeals show that party litigants have fewer rights. The Scottish Government has clearly recognised that there is a problem. Mr MacAskill mentions the issue in the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill, but nowhere do the two words “party litigant” appear in the bill.

I believe that my petition could serve to support any further planned measures to bring relief in such cases, so I feel that it is in the interests of justice and of all party litigants for the committee to consider it.

The Convener: Thank you very much. If Mr Mclean would like to respond to any of the questions that we ask, I encourage him to catch my eye.You have probably dealt with my first question, but I will ask it anyway, just for the record. You mentioned the two-counsel rule, which seems to be crucial. Are you arguing that article 6 of the European convention on human rights, which is on the right to a fair hearing, is being breached?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: I am saying that a party litigant does not have the right to approach counsel. That is a breach of equality of arms, for which article 6 provides, so people’s human rights are being breached. A party litigant cannot approach counsel directly—they must go through a solicitor.

The Convener: My second question is about future legislation. You mentioned the Government’s Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill, which will be considered by the Justice Committee, and you hinted at what it could do. My understanding is that that bill will take away the two-counsel rule and that it will be for the inner house to decide whether there are sufficient grounds for someone to go to the Supreme Court. What is your view of that assessment? If the bill went through, would it solve your problem?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: No, it would not. The bill, which I believe was introduced on 6 February, does not mention party litigants, and I think that that is a gross problem. The phrase “party litigant” does not appear in the bill. Will the bill provide a big umbrella, under which everyone will fit, or will it provide for people who are legally represented? That is where the problem lies. If someone is not legally represented, how will they be able to go to the inner house, which is what it is proposed will happen?

The Convener: So you are arguing that the bill would not solve your problem.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: It would not cover party litigants.

The Convener: Okay—thank you for that.

Chic Brodie: I will begin with a general point, which does not relate only to the Public Petitions Committee. I am very concerned about how hard it is to get information out of the legal system in Scotland. Given that a number of approaches have been made and that hardly any replies have been received, I wonder what on earth is going on and how our legal system is being administered. People should at least have the decency to provide a reply, whether we are talking about the Lord President, the cabinet secretary or whoever. I leave that point lying.

What is your view of the proposed change, whereby someone would be able to approach the Faculty of Advocates, rather than having to have two solicitors approve their appeal to the inner house?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: At the moment, a party litigant has to get two signatures from Scottish counsel. That is where the problem lies. It is not possible to approach counsel, to go to the Court of Session to speak to counsel or to phone up counsel. They will have nothing whatever to do with you. It is necessary to go to a solicitor, who will go on your behalf to counsel.

Chic Brodie: I am sorry to interrupt, but in the petition you say:“only a solicitor practising in Edinburgh can contact a counsel.”

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Yes, that is another problem.

Chic Brodie: Where is the evidence for that?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: I believe that a solicitor from Glasgow submitted a petition a few months ago on the problem whereby a Glasgow solicitor has to instruct an Edinburgh solicitor in order to be able to go to the Court of Session. That is my understanding—that is the way in which the situation was explained to me. I went to a Glasgow solicitor who told me that. A solicitor cannot do that unless they have what I think is called the right of audience.

Chic Brodie: If that is the case, I find it most disconcerting. I have one last question. I know that we cannot go into the detail of your case, but do you agree that there has to be some filtering out of the number of cases in which the inner house might be approached, other than through the two solicitor rule? Have you any idea how that process might be performed?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: We do not know how long it will take for the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill to go through. It could be changed so that a party litigant who had gone through the Court of Session, appealed and lost their appeal would have the right to go directly to counsel.

It might be argued that there is already a free legal services unit. You can go to various agencies and ask them to make an application to the FLSU, which is run by certain advocates on a pro bono basis, but the unit can give people only three days. Many cases have taken years to go through the Court of Session, so three days is not enough. It takes more than three days to read the case and do research. The FLSU does not cover a party litigant in that regard.

Angus MacDonald: I appreciate your bringing these anomalies to the Parliament’s attention. It seems unfair that party litigants can approach counsel only through a solicitor, which defeats the purpose of the individual having the right to represent themselves.

I agree with you that the 42-day period for filing a notice of appeal seems excessively short. You did not really touch on that in your preamble. It has been noted that the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill seeks to introduce a provision that requires litigants to seek leave to appeal, rather than there being a requirement for two counsel to certify appeals. I understand that, in the bill, there is no intention to increase the 42-day period for filing a notice of appeal, although I could be wrong. Clearly you would wish that period to be increased.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Yes, if possible.

The Convener: As you probably know, we get a briefing from our information service—SPICe—on every single petition that is lodged. Our briefing states:“the Faculty of Advocates suggests that party litigants can approach the Faculty directly for assistance in this regard.”Do you have any comments on that?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: I have tried—and I know of three other party litigants who have tried—to address the Faculty of Advocates. The faculty does not reply.I sent a freedom of information request on the matter eight weeks ago, but I have not had a reply. As it says in its response to the Government consultation, the Faculty of Advocates finds party litigants “burdensome”. That is shocking. That means that we are not on a level playing field where everyone has the right to represent themselves. The system does not work.

The Convener: Is it reasonable to say that there is an outstanding issue around the Faculty of Advocates? We have picked up that it is offering to provide help and advice, but you are saying that you have found it difficult to get a response.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: It does not respond. That is where the free legal services unit comes in, which the Faculty of Advocates runs on a pro bono basis. The problem is that you have to find an agency, which could be Strathclyde law clinic or a citizens advice bureau, to make the application to the free legal services unit at the advocates library, and somebody will read it and say yes or no. However, as you can have only three days from the unit, and they take perhaps one day to read it and one day to do a bit of research, when will they stand in court and do the proof? There is no time. I hate to say this, but I feel that the Faculty of Advocates is just doing some window dressing and not addressing the problem. It does not respond to freedom of information requests.

I made an FOI request to the Supreme Court in London, which told me that not one party litigant from Scotland has ever been able to appeal. Why?

The Convener: I am not putting words in the mouth of our information service, but the general comments that we get through it are that the two advocates or counsel that you refer to will not sign an appeal unless they feel that there is a valid issue in law for the case to go to the next stage. That is the general legal position. Do you accept that that summarises where we are in the law?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Yes. The average length of case for the majority of party litigants is 11 years. I think that they have a point in law; otherwise, they would not have kept going for more than 11 years and their cases would have been thrown out of court. It is up to the party litigant to put forward the points of law to the advocate, which is not done lightly. However, they are not paying for the advocate or counsel, and I think that money really speaks.

The Convener: Mr McLean, do you have anything to add at this point?

Gordon Mclean: No.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Might I add something?

The Convener: Sure.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: I approached Lord Gill, but he simply sent a letter from his secretary telling me to go www.supremecourt.com. I did not ask for legal advice and I did not ask any unusual questions. I just asked about paragraph 1.8, but he would not answer me. Everybody whom I have asked in the legal system has told me to go to paragraph 1.8.

The Convener: Thank you for that. We have come to the end of questions, but we want you to stay while we look at how to deal with your petition.

You have raised a lot of very interesting points and shown that there is real frustration among party litigants, particularly about getting to the Supreme Court and using ECHR. Normally, the committee wants to go as far as we can with each petition. There are some exceptions, however, such as where another committee is looking at legislation that is relevant to the petition. As you will know, the Justice Committee is looking at the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill. It would therefore make a lot of sense for us to refer the petition to that committee so that it can consider whether the bill could help you.

My advice to the committee is that we refer the petition as soon as possible to the Justice Committee so that, as part of its consideration of the bill, it can look at the issues raised by the petitioner. I think that the petition raises quite a lot of questions, and I would be pleased if our colleagues in the Justice Committee could have a look at it. However, that is a matter for committee members to decide. What are members’ views?

Chic Brodie: I agree with your view. However, sometimes we forget why we are here, which is to respond to people who have genuine issues. I fail to understand why the powers that be are not responding, at least with some degree of courtesy, to the petitioner. Personally, I find it wholly unacceptable that information is not being provided—there is not even the courtesy of a letter. I hope that the message that we send from here, whether formally or not, is that we are here to represent petitioners, whether they are right or wrong, and that they should be treated with courtesy, no matter what part of Government is involved. Frankly, in my opinion, some of the answers—indeed, the lack of answers—that have been received in this case are wholly unacceptable.

The Convener: Mr Brodie makes an excellent point. Do members agree with the recommendation that we refer the petition to the Justice Committee? Members indicated agreement.

The Convener: As the petitioners will have heard, we are keen to ensure that the committee focusing on the bill also focuses on your petition. We will therefore arrange for it to be transferred immediately to the Justice Committee, which will keep you up to date with progress. The petition is still active in the Scottish Parliament; it is simply being referred to the appropriate committee that is considering the legislation.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: When I went to my local MSP, Michael Russell, he informed me that he had spoken to Kenny MacAskill, who said that the law will be changed when Scotland gets independence.

The Convener: Right.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: I just wanted to put that on the record.

The Convener: I have to say that that is slightly beyond my pay grade. Mr Russell is entitled to his comments but, as far as what the Public Petitions Committee can do—

Jackson Carlaw: I am sorry, convener, but I must ask the witness whether that comment was communicated to her in writing.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Well, my husband was there—

Jackson Carlaw: But do you have written confirmation of it?

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: No.

Jackson Carlaw: It would be very interesting if you were able to obtain that commitment in writing and shared it with the committee.

The Convener: Thank you, Mr Carlaw.

As I have said, the petition is still active and will be referred to our colleagues on the Justice Committee, who will consider it alongside the bill.I thank the petitioners for coming along and raising a number of very worrying points. I hope that the Justice Committee will be able to look at the matter in more detail.I suspend the meeting for a minute to allow our witnesses to leave.

Gordon Mclean: Thank you.

Kathie Mclean-Toremar: Thank you very much for listening to us.

The Committee agreed to refer the petition, under Rule 15.6.2, to the Justice Committee as part of its scrutiny of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Bill.

Contrary to profession’s view, evidence from clients suggests dishonesty in Scots solicitors is rewarded, not punished. SCOTTISH solicitors “make false representations in order to improve their client’s position, not necessarily their own”. This was a claim made by solicitor Alistair Cockburn, Chairman of the Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal (SSDT) in response to key questions raised by BBC Journalist Sam Poling in the recent investigative programme Lawyers Behaving Badly.

Contrary to profession’s view, evidence from clients suggests dishonesty in Scots solicitors is rewarded, not punished. SCOTTISH solicitors “make false representations in order to improve their client’s position, not necessarily their own”. This was a claim made by solicitor Alistair Cockburn, Chairman of the Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal (SSDT) in response to key questions raised by BBC Journalist Sam Poling in the recent investigative programme Lawyers Behaving Badly.